Kupfermuckn vendor Ramona: “I thought to myself, ‘if I stay in Romania, I will die’”

By Daniela Warger

- Vendor stories

Romanian-born Ramona is finding life tough these days: she is undergoing treatment for breast cancer and works as a Kupfermuckn vendor, in Linz, Austria, when her health allows. She and her husband left Romania with their young son a decade ago after experiencing prejudice because of their Romani background. Nowadays, Ramona is doing everything she can to stay strong for her family, which welcomed daughter Vanessa in 2020.

It’s all a bit much just now,” Ramona tells me, speaking in good German as she takes a seat in the office of the Kupfermuckn street paper and absent-mindedly stirs her tea. These days she wears a scarf to cover her head. “It can get really cold when you’ve lost your hair,” she says with a shy smile. “Especially when I am out selling Kupfermuckn.” Ramona says that she would have been left high and dry without the street paper. Breast cancer means that Romanian-born Ramona cannot hold down a job at the moment; she just does not have the strength needed to do so. Ten years ago, she still had dreams. But these were quickly shattered – even Austria offers little quality of life for her and her children.

No prospects in Romania

There was no work for people like her in her Romanian hometown of Timisoara, some 80 kilometres from the Hungarian border. “Everything was OK there before,” Ramona recalls. By “before”, she means the time before the revolution against the dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu, which started in her hometown. Before that history-changing event, 18-year-olds could still live a relatively worry-free life. “The government gave everyone a roof over their head and food stamps,” Ramona recalls, of the years before the revolution. “No one had to starve. And the apartments were relatively warm.” Everyone got the same, she says. Early every morning there would be two litres of milk, a big hunk of bread, and butter for her four siblings and her parents. Her mother would get up at four in the morning every day to join the queue. “It wasn’t a lot, but we didn’t ask for anything more anyway,” she says.

A revolution with consequences

Ramona’s memories of the revolution are still very vivid. “The fighting was brief, but terribly fierce,” she says. “Anyone who lingered outside was shot by the military.” Ramona had just turned eight years old at the time. Fearing for their lives, they fled to her aunt’s home in a neighbouring village. Her father, however, had to stay in the town for work. He was hit and seriously wounded on his way home. “They shot away his elbow,” Ramona says. “It was terrible, but he survived.”

Many people were killed, she continues. The dead are buried in a mass grave in the central cemetery, with the words “They died for the town” as an epitaph. “Much of the town was in ruins,” Ramona continues. “Many houses had bullet holes in them that you can still see today.”

Unfortunately, life changed completely after the revolution. “It’s true that you could get hold of everything that was available in the West,” she explains, “but work became almost impossible to find.”

The gap between rich and poor has since widened even further. Ramona and her family find themselves on the poor side. “We are now discriminated against because we are Romani,” she says. Incidentally, she is proud to be called a “gypsy”. “It’s not an insult,” she is keen to clarify. However, Romani are shut out from everything in Romania. “There are no jobs for us, no decent education, no health insurance, and no support from the government either.” Her hometown might present a glitzy exterior to the outside world, with all its international boutiques, but the dark side is also not far below the surface. Ramona speaks of orphans begging, drug addicts, sick people who cannot afford medical treatment, and countess homeless people living on the streets.

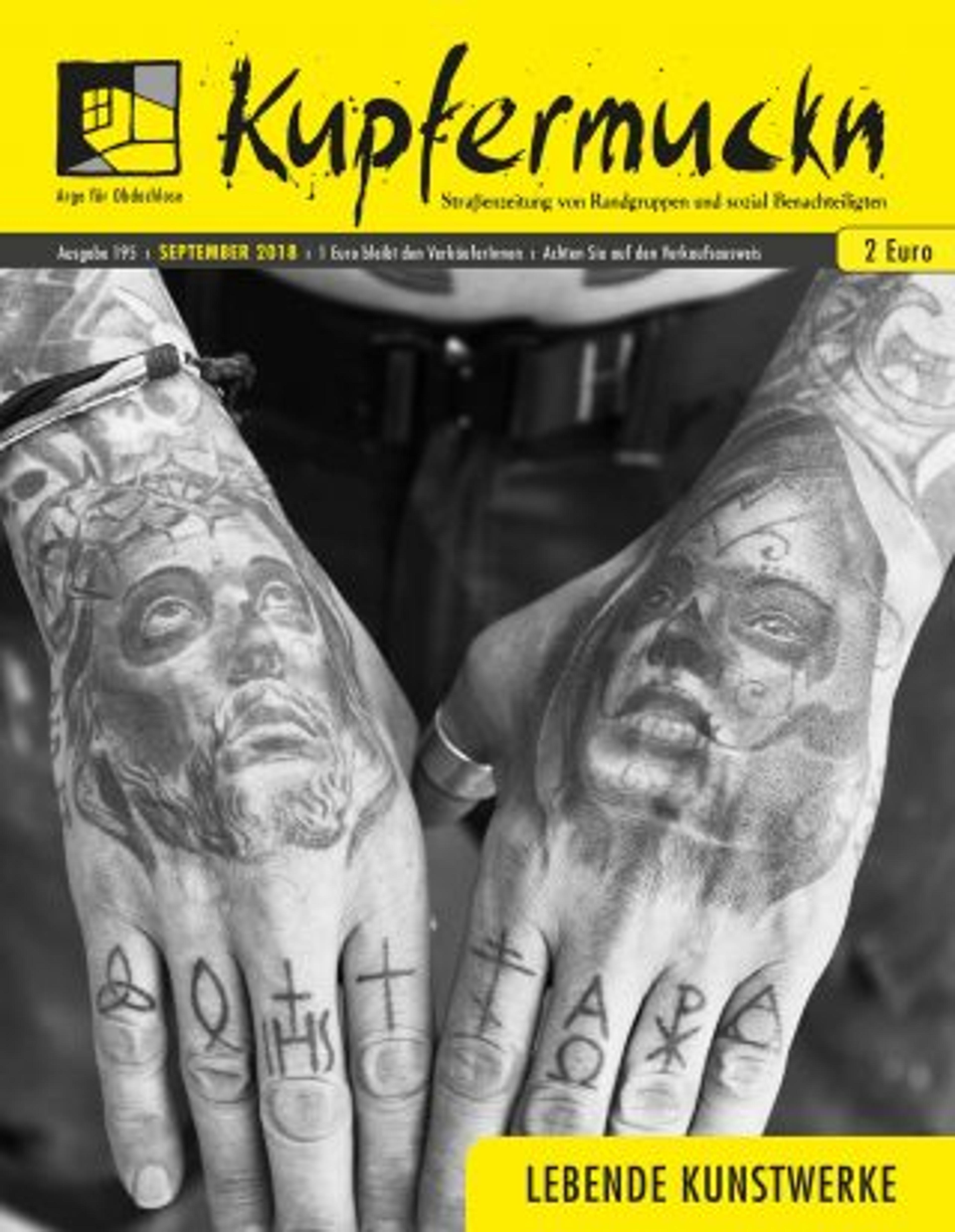

Photo by Daniela Warger

Shattered dreams

When her son came into the world twelve years ago, a thought came into Ramona’s head: “My son has to have a different life. There is no future for him here in our town.” For that reason, she and her husband decided to leave Romania when their son was two years old. The young family found a small flat in Ansfelden (in the Linz region of Upper Austria). Her husband got a job with the postal service while she worked as a cleaner and took on an extra job as an assistant cook. Their rent was 400 euros. At that time, they were still able to keep their heads well above water with temping and cleaning jobs.

In 2018, they moved back to Romania. “My mother was very ill, and I wanted to be by her side,” says Ramona. In 2020, her daughter was born. “Vanessa has brought the greatest happiness to my life,” she tells me, beaming. But then fate dealt a cruel blow. “In November last year, the baby kicked out and she hit my breast,” Ramona remembers. “It hurt so much; it felt like someone had stabbed me.”

Seven breast tumours

The pain got worse. Ramona went to the doctor. As she was not covered by health insurance, she had to dig deep into her own pockets to pay for the consultation. The mammogram she needed cost an additional 100 euros. She was told that the tumour had already spread. Ramona thought to herself, “If I stay here, I will die”. Out of necessity, she moved back to Linz with her daughter while her husband and son stayed in Romania. She now receives professional medical attention in the Hospital of the Sisters of Charity. She has chemotherapy once a month and will soon have an operation to remove part of her right breast, where seven tumours have been found.

Surviving, not living

Ramona is fighting for her very survival. She can barely make ends meet on 18.80 euros per day and the support provided by her husband. For a long time, she lived in a shabby apartment in an old building, without the protection of a lease. The walls were covered in mould. It was damp and dark, she recounts. To make things worse, she then received the heating bill. She was hit with a top-up payment demand for more than 700 euros. The rent was already very high, at 630 euros. Desperate, she turned to ARGE SIE, the women’s project operated by the ARGE association for the homeless.

Since then, things have been looking up. Hope is beginning to awaken in her again. Thanks to the ARGE SIE support workers, Ramona has been re-homed in a crisis flat. She is able to pay her debts off little by little.

Staying strong for her children

In order to earn money, and as far as her health allows, Ramona goes out and sells a few copies of Kupfermuckn – fifteen copies a day at most; it is just not possible for her to do more. And she simply cannot do anything at all in the days following her chemotherapy treatment.

Things have taken a turn for the better, however, since she has been selling the papers. She is delighted to being receiving help from ARGE SIE, and getting better is now her top priority. She wants to stay strong for her young daughter and for her son. Luckily, she has a close friend who looks after Vanessa when she is feeling very ill or if she has to spend a couple of nights in hospital.

“I am often very tired and exhausted, but I believe I can get better,” Ramona tells me at the end of our conversation. “My belief in God keeps me strong.”

Translated from German via Translators Without Borders

Support our News Service

We believe journalism can change lives, perceptions, and society - underpinning democracy for a more equitable world. Learn more about the INSP News Service and how to support it here.